The Incredible Story of the World’s 1st Illegal Underwater Surgery

I don’t know how other branches instill passion in their medics, but in the US Navy it’s done by telling the legends of our craft. The heroes who’ve gone before us to set the example and show us what being a combat medic means.

One of these who inspired me early in my career was the story of Pharmacist’s Mate 1st Class Wheeler Lipes, who, while at sea and underwater in enemy territory, preformed an illegal surgery that saved the life of his shipmate.

This story was first told to me during Field Medical Training during a cold and rainy day in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The rain had caused some sort of delay in training and while we were sitting and waiting, our instructor told us what it meant to be a good “Doc.”

We were there for a while and heard one grisly tale after another, but one that always stuck with me was an example how a good medic is resourceful.

Lipes joined the Navy at age 16 in 1936 giving him the chance to learn his trade before America entered WW ll December 11th, 1941. During this time, he worked closely with surgeons and assisted in numerous appendectomies. Just before moving to submarines, one of the doctors who taught Lipes pulled him aside:

“You never know what’s going to happen in a submarine. One of the things you may face is appendicitis.” The doctor then went on to give the young Lipes tips for success should he ever need to perform the operation at sea.

On the 4th deployment of Lipes sub into the South China Sea, this advice proved more prophecy.

Thousands of miles away from any port, the USS Seadragon conducted combat patrols, leaving Australia’s port of Fremantle on August 26th, 1942.

The deployment was uneventful until September 8th, when 19-year-old, Petty Officer 3rd Class Darrel Rector approached Doc Lipes and reported abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and a fever. Lipes sent him to his rack to rest up but after a few days, he was getting worse.

The 23-year-old corpsman recognized the classic signs of appendicitis and grew worried his patient might not survive the voyage, and said so to the sub’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander William Farrall, on September 11th.

Once he understood the situation, Commander Farrall went to speak with Rector, still writhing in his rack.

When asked if he consented to surgery, Rector replied:

“Whatever the doc feels has to be done is okay with me,”

The skipper then turned back to Lipes. Could he do the operation?

“Yes sir, I can do it,” said Lipes, “but everything’s against us. Our chances are slim.”

“I fire torpedoes every day and some of them miss,’ Lipes later recounted the Skipper’s reply.

“I told him that I could not fire this torpedo and miss. He asked me if I could do the surgery and I said yes. He then ordered me to do it.”

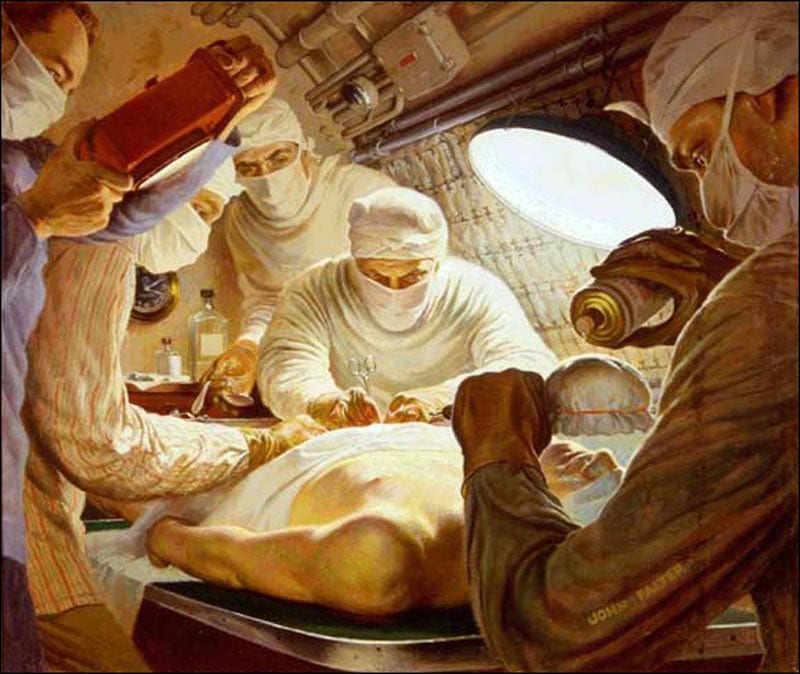

Lipes set to work gathering everything he’d need to perform an impromptu and cobbled together operating room. The bolted down Wardroom table was just long enough to fit the lanky sailor, so it was commandeered for the surgery.

“I had no blood pressure apparatus. I had no access to a laboratory. I couldn't do a blood count. I couldn't do a urinalysis. I didn't have a microscope. I had no intravenous fluid, no nothing. Submarines went to sea without adequate equipment and support and with very few basics,” Lipes recalled. Military Medicine

The sub’s medical kit contained a few useful items, like sutures, scalpels without handles, and a pack of hemostats. Also included was a substantial supply of 3 liters of ether anesthesia, making the operation possible, but of course, lacking a way to administer it.

What Lipes didn’t have, he improvised, turning 5 bent galley spoons into retractors, sanitizing instruments with Torpedo Juice, and turning gauze and a metal tea strainer into an ether administration mask.

Meanwhile, Skipper Farrall ordered the sub into calmer waters and descended to a depth of 120 ft below the surface of the waves to keep the sub steady.

The skipper attended the operation and documented the procedure:

Communications officer, Lieutenant Franz Hoskins began ether administration at 1046, and the first incision at 1107.

Shortly after beginning, Lipes ran into yet another problem: The patient didn’t seem to have an appendix. This worried the inexperienced young surgeon.

Lipes recalled many years later:

“When I got to the appendix, it wasn't there. I thought. ‘Oh my God! Is this guy reversed?’ There are people like that with organs opposite where they should be. I slipped my finger down under the cecum — the blind gut — and felt it there.

Suddenly I understood why it hadn't popped up where I could see it. I turned the cecum over. The appendix, which was 5 inches long, was adhered, buried at the distal tip, and looked gangrenous two-thirds of the way. ‘What luck,’ I thought. ‘My first one couldn't be easy.”

Sure, it took longer than it might for an experienced sawbones, but the job was done, and done well, with the last stich thrown at 1322. Petty Officer Rector recovered quickly and was back on duty within a few days. His appetite returning with such gusto, the sub’s cook remarked:

“Doc, you must have sewed him up with rubber bands, the way he eats.”

Rector was closely examined by the submarine squadron medical officer (MO) after the USS Seadragon returned to port 6 weeks later and was determined to be perfectly healthy with the incision healed nicely. His life had no doubt been saved, the MO said, by the quick actions of Doc Lipes and the Seadragon crew:

From: The Squadron Medical Officer

To: The Chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery

Via: The Commander Submarine Squadron Two

Subject: Appendectomy aboard a submarine, special report of.

“… While it is by no means desirable to encourage major surgical procedures on naval personnel by other than qualified surgeons, yet in this particular instance, it appears that deliberation and cautious restraint preceded the operation; the operation was performed under difficult circumstances and with pioneering fortitude and resourcefulness; and that the result was entirely satisfactory.

Lipes was at first hailed a hero. He was, after all, a testament to the obviously effective training program which produced him. A shining example of resourcefulness and medical prowess that all corpsmen could aspire to.

But not everyone was pleased with what he’d accomplished, regardless of success.

Word of the improvised appendectomy spread in a flash across the Navy fleet and soon reached the US Surgeon General himself, Rear Admiral Ross McIntire, who was less than impressed with Lipes’ resourcefulness.

In a rage, the Admiral allegedly threatened to have Doc Lipes arrested and court martialed. Lipes had clearly operated outside his scope of care. Surgery is only to be done by qualified surgeons in well-lit operating rooms and not by untested medics with spoon retractors in a dimly lit submarine.

He did not appreciate the young medic’s shining example in the slightest. Other un-qualifieds would surely attempt this same procedure now that word was out it could be done. And, in fact, two more submarine appendectomies were reported soon after, in December of 1942.

George Weller, a reporter for the Chicago Daily News picked up the story and received a Pulitzer Prize for the article he wrote detailing the undersea events.

The story was unique enough to be added into the 1943 movie, Destination Tokyo, starring Cary Grant

Although he enjoyed some notoriety from his makeshift surgery, Lipes' actions were largely ignored by big Navy, who decided in the end not to destroy the sailor as an example of how to stay in one’s lane as a medic and not go beyond the scope of care.

Some reports say that Lipes' military career suffered for his actions and advancement was slow due to the higher ups disapproval. Whatever the case, he enjoyed a lengthy career in the Navy, retiring in 1962 with the rank of Lieutenant Commander.

Despite Lipes’ best effort onboard the sub, Petty Officer Rector died a few years later in 1944 when a faulty torpedo, fired from his own battle sub, arced back and returned to strike the stern of the vessel, sinking it and killing all but 9 of the crew.

Lipes later told Navy History and Heritage Command in 1987:

“I was on an airplane recently and the man next to me was reading a magazine containing one of those Ripley's Believe it or Not's. It told of a submarine sailor who removed the appendix of a shipmate. This guy turned to me and said, “Can you believe that?” I read it, shook my head, and said, “Don't you believe a word of it.”

3 months prior to his death in 2005, the US Navy finally recognized his excellent work after intense lobbying by Lipes’ family and supporters. He was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal at a ceremony in Camp Lejeune, just 2 years before I arrived to hear the story at Field Medical Training Battalion.

i remember seeing the incident portrayed on the series “The Silent Service” in the 50s “The Silent Service” was a half hour program about the US Navy Submarine Service , the series was a lot similar to another series in the 50s “Navy Log” both had the assistance of the DoD and dept of the Navy